Delegates are a way to declare accepted properties and returntype of methods, without having to write the actual code for the method. This can be handy when the method of an object depends upon the actual object itself.

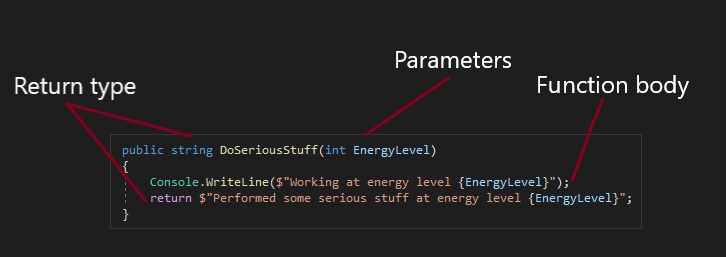

When writing methods you define returntype, parameters and the actual code to be performed, the function body.

But in some cases when the method should depend on the instance of the class, it can be a problem to specify the actual function body.

Imagine we have a class Person with the string properties FirstName, LastName, and a List<string> property NameHistory for which we instantiate two objects: NoBody and SomeBody. We would like to be able to change the name of the people so we write a method ChangeName for this, but can’t decide how to write the code to save the history of names. Datastorage is precious and there are lots of nobodies in the world, so we can’t keep track of their names in a NameHistory. But we should keep a detailed record of this for a person that’s a somebody.

class Person

{

public string FirstName { get; set; }

public string LastName { get; set; }

public List<String> NameHistory { get; set; }

public void ChangeName(string NewFirstName, string NewLastName)

{

...?

}

}

Person Nobody = new Person { FirstName = "No", LastName = "Body" };

Person SomeBody = new Person { FirstName = "Some", LastName = "Body" };Of course an easy way would be to implement a property bool IsSomebody and use an if-statement in the ChangeName function. But what if we end up having lots of different rules for different instances of person? A delegate would solve this problem.

Create a delegate

A delegate is created with the keyword delegate followed by it’s returntype and parameters. You can then create an instance of this delegate, load it up with a method and invoke the method by calling the instance of the delegate.

class Person

{

...

//Defenition of a delegate that returns nothing and takes a Person object as a parameter

delegate void StoreHistoryDelegate(Person p);

//A default method is given that takes itself as a parameter and does nothing. Using a lambda-expression to define the

//method.

public StoreHistoryDelegate StoreHistory = p => {};

public void ChangeName(string NewFirstName, string NewLastName)

{

//The delegate is used in the method to store history of name

StoreHistory(this);

//The names are changed

this.FirstName = NewFirstName;

this.LastName = NewLastName;

}

...

}We can then override the method contained in the instance of the object if we want to, and define a new function to handle the history storing.

Person Somebody = new Person { FirstName = "Some", LastName = "Body" }

Somebody.StoreHistory = (Person p) =>

{

//Add datetime and previous name to the history list

p.NameHistory.Add($"{DateTime.Now}: previous name is {FirstName} {LastName}");

}